Treatment of pain-related suffering requires knowledge of how pain signals are initially interpreted and subsequently transmitted and perpetuated.

Clinical pain is a serious public health issue.Our understanding of the neural correlates of pain perception in humans has improved with the advent of neuroimaging. Relating neural activity changes to the varied pain experiences has led to an increased awareness of how factors (e.g., cognition, emotion, context, injury) can separately influence pain perception.

It has been suggested that the brainstem plays a pivotal role in gating the degree of nociceptive transmission so that the resultant pain experienced is appropriate for the particular situation of the individual.

Pain that persists for more than three months is defined as chronic and as such is one of largest medical health problems in the developed world. While the management and treatment of acute pain is reasonably good, the needs of chronic pain sufferers are largely unmet, creating an enormous emotional and financial burden to sufferers, carers, and society.

The mechanisms that contribute to the generation and maintenance of a chronic pain state are increasingly investigated and better understood. A consequent shift in mindset that treats chronic pain as a disease rather than a symptom is accelerating advances in this field considerably.

Pain is a conscious experience, an interpretation of the nociceptive input influenced by memories, emotional, pathological, genetic, and cognitive factors. Resultant pain is not necessarily related linearly to the nociceptive drive or input; neither is it solely for vital protective functions. This is especially true in the chronic pain state. Furthermore, the behavioral response by a subject to a painful event is modified according to what is appropriate or possible in any particular situation. Pain is, therefore, a highly subjective experience “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage.”

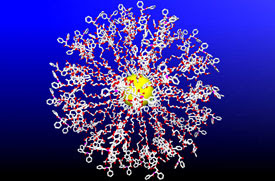

By its very nature, pain is therefore difficult to assess, investigate, manage, and treat. Figure 1 (above) illustrates the mixture of factors that we know influence nociceptive inputs to amplify, attenuate, and color the pain experience.

Because pain is a complex, multifactorial subjective experience, a large distributed brain network is subsequently accessed during nociceptive processingm and was first described this as the pain “neuromatrix,” but it's now more commonly referred to as the “pain matrix”; simplistically it can be thought of as having lateral (sensory-discriminatory) and medial (affective-cognitive-evaluative) neuroanatomical components. However, because different brain regions play a more or less active role depending upon the precise interplay of the factors involved in influencing pain perception (e.g., cognition, mood, injury, and so forth), what comprises the pain matrix is not unequivocally defined.

For both chronic and acute pain sufferers, mood and emotional state has a significant impact on the resultant pain perception and ability to cope. For example, it is a common clinical and experimental observation that anticipating and being anxious about pain can exacerbate the pain experienced. Anticipating pain is highly adaptive; we all learn in early life to avoid hot pans on stoves and not to put your finger into a candle flame. However, for the chronic pain patient it becomes maladaptive and can lead to fear of movement, avoidance, anxiety, and so forth.

Another negative cognitive and mood affect that impacts pain is catastrophizing. This construct incorporates magnification of pain-related symptoms, rumination about pain, feelings of helplessness, and pessimism about pain-related outcomes, and it is defined as a set of negative emotional and cognitive processes. A study on fibromyalgia patients found that pain catastrophizing, independent of the influence of depression, was significantly associated with increased activity in brain areas related to anticipation of pain (medial frontal cortex, cerebellum), attention to pain (dorsal ACC, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex), emotional aspects of pain (claustrum, closely connected to amygdala), and motor control.

Clearly, these results support the notion that catastrophizing influences pain perception through altering attention and anticipation, as well as heightening emotional responses to pain.

It is interesting to speculate whether activity in such “emotional” brain regions due to chronic pain impacts performance in tasks requiring emotional decision making. A card game developed to study emotional decision making, chronic pain patients displayed a specific cognitive deficit compared to controls, suggesting such an impact might exist in everyday life.

Such experiments are hard to reproduce in animal studies.

As the problem of pain and the key role of the brain becomes increasingly well recognized, more research is being directed toward a better understanding of the underlying mechanisms. Some of the newest and more novel areas of investigation are briefly summarized

here.The recent finding that significant atrophy exists in the brains of chronic pain patients highlights the need to perform more advanced structural imaging measures and image analyses to quantify fully these effects.

Determining what the possible causal factors are that produce such neurodegeneration is difficult. Candidates include the chronic pain condition itself (i.e., excitotoxic events due to barrage of nociceptive inputs), the pharmacological agents prescribed, or perhaps the physical lifestyle change subsequent to becoming a chronic pain patient.

_________________________________________________________

Backache Sufferers Who Fear Pain Change Movements from Science Daily_________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________

Cancer-clogging drugs loaded onto nanospheres from Rice University

Cancer-clogging drugs loaded onto nanospheres from Rice University